The summer is winding down and so too is the market's outlook for inflation. The 10-year forecast for inflation, based on the yield spread between nominal and inflation-indexed Treasuries, dipped under 1.6% last week—the lowest level in about a year.

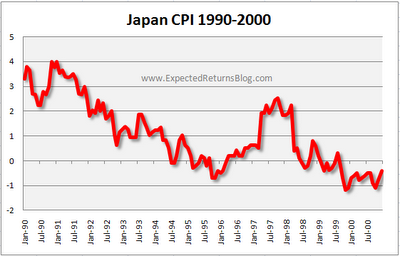

That's a disturbing sign for a number of reasons, starting with the recognition that this is supposed to be an economic recovery. The recession technically ended last year, or so many economists opine. If so, inflationary pressures at the very least should be holding steady if not rising. And for a while, that was the trend. Through the end of this past April, inflation expectations were on the march, rising to roughly 2.45%, up from something approximating zero in late-2008, when the financial crisis was raging. But as the chart below reminds, something changed in May and the D risk was on the march once more. The recovery hit a wall of turbulence and the macro outlook has been suffering ever since.

The challenge was compounded earlier this month when the Federal Reserve disappointed the market with a tepid response to deflation's mounting momentum. Since the last FOMC meeting on August 10, the Treasury market's 10-year inflation forecast has fallen by nearly 20 basis points. If the Fed's last FOMC statement was designed to arrest the market's worries about deflation, the effort looks like a failure so far.

But talk is cheap. What of the central bank's actions? Is monetary policy reacting to the rising to the challenge of the D risk? Perhaps. Recent data on monetary aggregates suggest a change may be unfolding as we write. The monetary base (defined by MZM money stock) turned up recently after a period of decline. As the second chart below indicates, MZM has been rising in recent months.

So far, however, the increase in MZM hasn't reversed the year-over-year percentage change. As the next chart shows, MZM's annual pace is still negative, as it's been for most of this year.

No wonder that long Treasuries have been soaring in recent months. The threat of deflation has motivated the crowd to bid up prices on government bonds. The iShares Barclays 20+ Year Treas Bond (TLT), for instance, has climbed nearly 20% since late-April, roughly the start of the current worries over the D risk.

For investors, the burning question is whether the D trade has legs? There's lots of positive momentum to argue in the affirmative. But it'd be a mistake to assume that deflation is a done deal. Yes, the Fed has stumbled and let worries about future prices take a tumble. But the game isn't over. The central bank can still change the market's expectations, but it's going to be harder to gain traction and the clock is ticking. Remember, this is all about managing expectations. Let's not forget that the Fed could, if it was so inclined, push long rates much lower by printing money. There are some very good reasons for why Bernanke and company are reluctant to roll out the nuclear option. But events may be set to overwhelm otherwise cautious thinking on matters of monetary policy.

Meantime, there's quite a bit of risk embedded in the D risk trade, on both sides. It's getting harder to dismiss the possibility that inflation expectations will continue to shrink. At the same time, the easy money in going long government bonds may not be so easy if the Fed chooses to get tough with the deflationary momentum. Since no one is really sure how all this will play out, this is no time to bet the farm, one way or another. We're in uncharted territory. Invest accordingly.

This article has been republished from James Picerno's blog, The Capital Spectator.